The Congressional Hackathon that took place this past Constitution Day on September 17, 2025, is a rarity in today’s Washington. Civic minded citizens joined with congressional staff in a day-long discussion inside the U.S. Capitol on strengthening Congress by improving and democratizing its technology. More information from the event, including video and a report, will be published on the Legislative Branch Innovation Hub.

The bipartisan nature of these events is a recurring theme, with senior Republicans and Democrats always offering opening remarks and providing space and support inside Congress. Indeed, the Speaker broke news at the Hackathon, announcing the House would be distributing up to 6,000 user licenses to congressional staff to use Microsoft’s M365 Copilot AI-powered chatbot for a year.

This is the seventh such Congressional Hackathon, with the first organized back in 2011. This iteration also was the fourth annual event in a row. I’ve been to them all and this event brought forth a groundswell of energy. Some of it came from the new coding breakout session, where almost 90 participants built tools side-by-side with congressional staff that provide insight and services to people in Congress, across government, and around the country. It reminded me of the civil society-organized hackathons of the 2010s that had so much energy and potential. We all owe a debt of appreciation to Speaker Johnson, Democratic Leader Jeffries, and CAO Catherine Szpindor for co-hosting.

Collaboration and culture change

One thing that has changed over the last fifteen years is the nature of congressional-public collaboration. In the beginning, some inside the congressional firmament were opposed to releasing data to the public. Even using the word “hack,” as in hackathon, was controversial. It took bipartisan leadership from Reps. Boehner, Cantor, McCarthy, Hoyer, Honda, Issa, and many others (including many unsung staff in political and non-political offices) to bend the arc. Now there is a culture shift, where many in the Legislative branch embrace modernization and the pockets of resistance have grown smaller and less influential.

Since the Hackathon became an annual event in 2022, presenters in its “lightning round” phase have steadily demonstrated more and more new projects and tools utilizing increasingly accessible legislative data. The origins of the culture change in Congress were a fight over whether data about legislation should be made publicly available. The result wasn’t just the publication of bulk access to legislative data, but the creation of the Bulk Data Task Force, a like-minded group of internal and external stakeholders that has been meeting quarterly for 13 years, encouraging and supporting technological modernization. One outcome was the Library’s granting of a longstanding public request for publication of congress.gov data as an API, which launched in October 2022. That API, its manager announced, has received 1.3 billion requests over its three year existence.

The Hacking Session

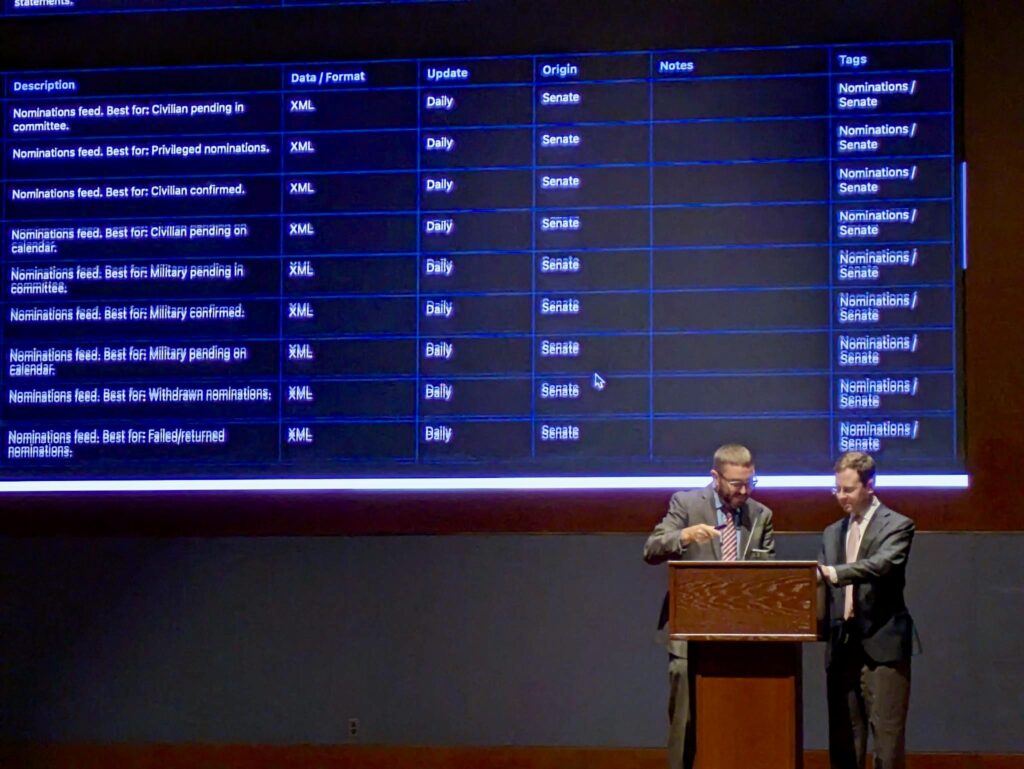

Last week, the progress made in bringing Congress into the digital age allowed developers for the first time to work on projects collaboratively during a morning session of the Hackathon. Some participants utilized a nascent Legislative branch data map, the existence of which had been requested by Appropriators. The map is an effort to identify across the Legislative branch the different sources for congressional data and drew rhetorical inspiration from the 2013 executive order on making open and machine readable the new default for government information, the 2018 Open Government Data Act, and advocacy from public-interest minded groups.

The map data was seeded from my 2023 biased yet reliable guide to sources of information and data about congress and collaborations from governmental members of the Congressional Data Task Force, although its GitHub repository quickly drew pull requests from hackathon participants as well. In other words, anyone can suggest items to add to the list of Legislative branch data sources and that list can point to official and non-official sources for data. This is important because it’s very hard to find data about Congress and a lot of the data is published in ways that are hard to reuse.

The map improves the findability of information and makes it discoverable when someone has done the hard work to refine that information into a useful format. It was my pleasure to present, along with the House Digital Service’s Steve Dwyer, on this new map that will catalyze the ability of technologists to build tools for and about Congress.

The data map became immediately handy during the coding portion of the hackathon, where Steve and I highlighted it to the coders who were present in the side room.

Among the hacking projects presented at the end of the day were:

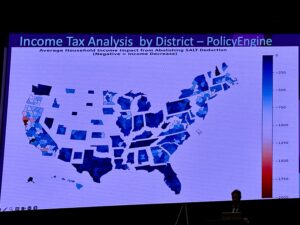

- Income tax analysis by congressional district, looking at the changes in taxation resulting from abolishing the SALT deduction, from Policy Engine. (Click through to see the visualizations.)

- CongressTrack, an effort to show the extent to which politicians keep their campaign promises.

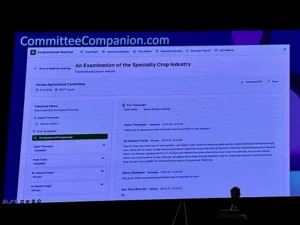

- Committee Companion, which uses AI to generate well-formatted transcripts from committee proceedings.

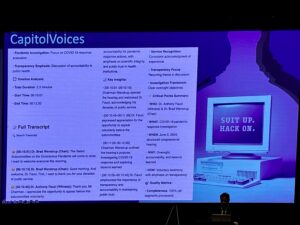

- Capitol Voices, which creates AI-powered congressional hearing transcription and analysis. It also identifies the speakers, themes, and sentiment analysis.

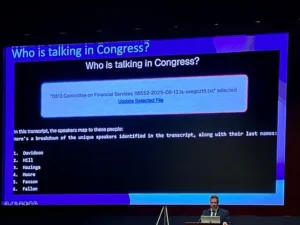

- Who is Talking in Congress, which breaks down the unique speakers identified in a transcript and their last names.

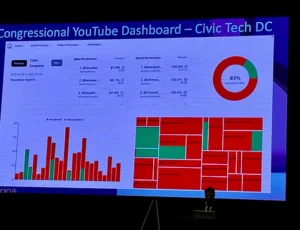

- Congressional YouTube Dashboard, a Civic Tech DC congressional-tech project that identifies how often House committees remember to publish the event IDs in YouTube videos. It is only through these event IDs that the Library of Congress identifies that a particular YouTube video is associated with a particular hearing. Notably, this project shows which committees are good at adding these IDs and which ones are lagging. Click through this link to see the visualization of the best and worst performing committees.

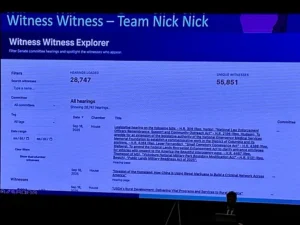

- Witness Witness, a proof of concept that creates a central tracker for all House and Senate hearing witnesses. They identified more than 55,000 unique congressional witnesses across 28,000 hearings. They wrote about their efforts on LinkedIn and posted this live demonstration. (Note: be patient while it loads… it’s worth it.)

- Witness Visualizer, which creates an interactive knowledge graph visualizing the relationships between (House) witnesses, committees, topics, and organizations.

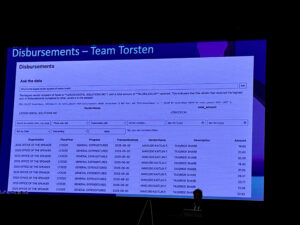

- Disbursements, which moves House Disbursement (i.e. spending) data into a database and provides the ability to search and filter the data as well as for users to ask questions (via AI) concerning the dataset.

Additional projects. A few presentations during the lightning round also have great relevance to the development of technology tools and we want to highlight them here.

- Hearings, presented by Abigail Haddad, is a great project that uses logic to identify the relevant YouTube video for a House hearing even when the committee has failed to include an event identifier. The live demo, focused on the House Energy and Commerce Committee, shows where the developer was able to match a hearing name with the correct YouTube video.

- Craig Butler from the House Digital Service and Pat O’Brien from the Senate Democratic Steering and Policy Committee demonstrated an extension of the old Capitol Bells App to digitize the old clock alert system in buildings on the congressional campus. This new system retrofits congressional clocks to transmit a digital signal when vote alarms sound, pushing out notifications and creating new entries in HouseCal.

- Bill Tracer, developed by Ruzanna Gaboyan and Philip Golczak, creates a track-changes comparison between the introduced and engrossed versions of a bill, with a particular focus on appropriations bills. (The House has built its own comparative print tool, but it’s not available to the public. GovTrack.us has a version of this, and Bill Tracer is working off GovTrack data.)

- We already mentioned the presentation from the Library of Congress’s Andrew Weber on the Congress.gov API, but we would be remiss not to mention that the API now has some CRS reports and House Roll Call votes. If you want new features for the API, a great place to request those features are on the Library’s GitHub repository, through the Library’s survey form, at the quarterly Congressional Data Task Force meetings, and at the Congress.gov public forum on September 30th.

Other presentations during the lightning round of the afternoon’s session demonstrated the innovative potential in using large language models and machine learning with the data available through the congres.gov API. Two projects, including one developed by a pair of Fairfax County high school students, addressed accessibility issues with government publications for people with disabilities. The nonprofit Policy Engine introduced their system that extrapolated the economic impact of bills onto the state and district level.

But Wait, There’s More

Congressional App Challenge Director Joe Alessi spoke about the program, where middle and high-school students from across the country built apps. The program is intended to foster an appreciation for computer science and STEM, with each congressional district choosing a winner and it culminating in an event, House of Code, in Washington, D.C.

There also were a series of breakout groups on various policy topics. Issues included modern committees, constituent services and communications, legislative data, AI, and cybersecurity. The groups met for an hour and reported out at the end of the conference. We were unable to collect all their recommendations, but you can learn more when the official hackathon report and video are released.

If you’re interested in prior hackathons, check out our write-ups:

- 2024: Read our summary, the official summary report, and watch the video.

- 2023: Read our summary, the official summary report, and watch the highlights video.

- 2022: Read our summary, the official summary report, and watch the highlights video

- 2017: Read our summary, the official summary report, and watch the highlights video and CSPAN coverage

- 2015: Read our summary, the official summary report, and watch the highlights video

- 2011: Read our summary, the official summary report, and watch the highlights video