Are democracies better at practicing open government than less free societies? To find out, I analyzed the 70 countries profiled in the Open Knowledge Foundation’s Open Data Index and compared the rankings against the 2013 Global Democracy Rankings. As a tenet of open government in the digital age, open data practices serve as one indicator of an open government. Overall, there is a strong relationship between democracy and transparency.

Using data collected in October 2013, the top ten countries for openness include the usual bastion-of-democracy suspects: the United Kingdom, the United States, mainland Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

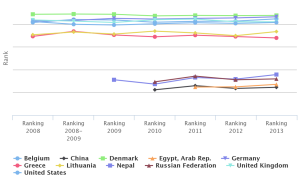

There are, however, some noteworthy exceptions. Germany ranks lower than Russia and China. All three rank well above Lithuania. Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Nepal all beat out Belgium. The chart (below) shows the democracy ranking of these same countries from 2008-2013 and highlights the obvious inconsistencies in the correlation between democracy and open data for many countries.

There are many reasons for such inconsistencies. The implementation of open-government efforts – for instance, opening government data sets – often can be imperfect or even misguided. Drilling down to some of the data behind the Open Data Index scores reveals that even countries that score very well, such as the United States, have room for improvement. For example, the judicial branch generally does not publish data and houses most information behind a pay-wall. The status of legislation and amendments introduced by Congress also often are not available in machine-readable form.

As internationally recognized markers of political freedom and technological innovation, open government initiatives are appealing political tools for politicians looking to gain prominence in the global arena, regardless of whether or not they possess a real commitment to democratic principles. In 2012, Russia made a public push to cultivate open government and open data projects that was enthusiastically endorsed by American institutions. In a June 2012 blog post summarizing a Russian “Open Government Ecosystem” workshop at the World Bank, one World Bank consultant professed the opinion that open government innovations “are happening all over Russia, and are starting to have genuine support from the country’s top leaders.”

Given the Russian government’s penchant for corruption, cronyism, violations of press freedom and increasing restrictions on public access to information, the idea that it was ever committed to government accountability and transparency is dubious at best. This was confirmed by Russia’s May 2013 withdrawal of its letter of intent to join the Open Government Partnership. As explained by John Wonderlich, policy director at the Sunlight Foundation:

While Russia’s initial commitment to OGP was likely a surprising boon for internal champions of reform, its withdrawal will also serve as a demonstration of the difficulty of making a political commitment to openness there.

Which just goes to show that, while a democratic government does not guarantee open government practices, a government that regularly violates democratic principles may be an impossible environment for implementing open government.

A cursory analysis of the ever-evolving international open data landscape reveals three major takeaways:

- Good intentions for government transparency in democratic countries are not always effectively realized.

- Politicians will gladly pay lip-service to the idea of open government without backing up words with actions.

- The transparency we’ve established can go away quickly without vigilant oversight and enforcement.