Legislation is how ideas are put into a format that Congress can process and transform into law. Some ideas are introduced again and again, but in different formats or at different times. Some bills in one chamber of Congress may have a nearly identical version introduced in the other. The same bill can be introduced again and again over multiple Congresses until it is enacted into law. Or a group of legislative ideas can be rolled together into a larger legislative package.

I like to think of ideas contained in legislation as legislative memes, which is a powerful way to understand what Congress is doing. We are working on a legislative tool, call BillMap, that allows you to track legislative memes as they move through Congress.

Richard Dawkins coined the term meme to describe ideas that are transmitted through a society. “Memes carry information, are replicated, and are transmitted from one person to another, and they have the ability to evolve, mutating at random and undergoing natural selection, with or without impacts on human fitness (reproduction and survival).”

Legislative memes contain ideas that are transmitted through Congress, replicate themselves into other legislation, are transmitted from Member to Member, and have the ability to evolve. They differ in that they do not mutate at random, but they can undergo a form of selection for political viability.

The concept of a legislative meme is important because members of Congress, staff, lobbyists, journalists, and others implicitly think about legislation as carriers for legislative ideas. We talk about “companion” legislation, that a bill has been “reintroduced,” or of legislative “packages” or “vehicles” containing many bills. From a technical perspective, every bill is an island — alone and discrete. But from a practical perspective, many bills are closely related, and we want to map these relationships because that allows us to understand where a bill has come from, what might be necessary for it to become law, and to understand what it does by gathering together legislative byproducts associated with the meme (like committee reports, votes, statements in the Congressional Record, press statements, CRS reports, and so on.)

Ari Hershowitz, a developer and attorney who is working on the BillMap project, recently wrote about his experiences developing software to identify bills that are related to other bills — to find and track these memes. Bill “relatedness” can not be determined by a single approach, but rather requires multiple techniques to capture different ways we can infer that that one bill is related to another — that they’re part of a common meme. We’ve developed these concepts together, and there are additional techniques we have yet to build into the software that can help more easily surface these connections.

The following blogpost is re-published from his website with his permission. If you want to see what BillMap, our meme tracking software, looks like from a user perspective, I gave a 10-minute presentation on BillMap in July to the Congress’s Bulk Data Task Force that you can watch here.

Finding similar bills in Congress

by Ari Hershowitz

Bills are often recycled. Most bills introduced in Congress are very similar to bills that have been introduced in a previous session. This reflects the imbalance between the number of bills that are proposed and bills that actually become law. Many bills are introduced for the purpose of “messaging” and their sponsors do not plan to get them passed; others simply don’t make it through the gauntlet of committees and votes that are required to make a new law. Each two-year session, up to 10,000 bills are introduced, of which a few hundred may pass.

When someone is reviewing a ‘new’ piece of legislation, they often want to know which other bills are similar to this one. They may want to know who sponsored the previous bills, what happened to those bills, and whether a bill’s content has already passed as a part of another bill. This research all starts with the question: which other bills are similar to this one?

I’ve been working on the problem of finding similar bills for a while, most recently with the BillMap project. The first challenge is figuring out what people really mean when they say two bills are ‘similar’. We often have an intuitive sense of what we mean when we say two things are similar, but rarely consider what objective factors make up that intuitive sense. And what we mean by ‘similar’ may change, depending on context. When we say ‘comparing apples and oranges’, we’re assuming a context in which those two common edible fruit are not considered similar. In that context, maybe an orange is similar to a lemon, but not to an apple. We’d need to investigate more to answer other questions: is a pear similar to an apple, an orange or neither?

For legislation, people often mean a variety of things when looking for ‘similar’ bills. Bills may share a legislative history, share sponsors, have similar titles, deal with similar subjects, or include much of the same text. Depending on the context, some combination of these factors makes two bills ‘similar’. At the same time, bills may differ in many of these factors, and still be considered similar. The most surprising case is where experts consider two bills to be similar, despite significant differences in their text.

For example, there are 38 bills that became law so far in the 117th Congress (the current one). One of these bills, H.R. 1448 has the title “Puppies Assisting Wounded Servicemembers for Veterans Therapy Act” or PAWS Act in the House. There is also a bill in the Senate, S. 613, with the same titles. These are considered similar because they have the same titles, serve the same purpose, and contain similar text in one section that creates a pilot program for dog training. However, comparing the text of the two small bills shows significant differences: the Senate version (below on the left) has a “Findings” section that makes up much of the bill, and is not found in the House version. The Senate bill also has a section at the end that is not in the House version. So two of the four sections are different, and the key section on dog training also has many changes. Nonetheless, they are both considered versions of the same ‘PAWS’ bill; because they are in different chambers, they may also be considered ‘companion’ legislation. Our goal is to be able to identify bills like this as ‘similar’, despite many of their textual differences.

Similar Text, Maybe Similar Bills

The difference between the House and Senate versions of the PAWS Act is a mild example of bills that are similar, but have many text mismatches. Sometimes the text of a bill may be completely rewritten, but still be considered ‘similar’ to the earlier version. In fact, comparing the text of bills is often not as helpful as other factors in finding similar bills. It’s also computationally very costly.

For the 10,000 or so bills introduced in any Congress, directly comparing the text of each pair of bills would require 10,000 x 10,000, or 100,000,000 comparisons. An average text comparison takes about 1 second, so comparing all bills could take 27,000 hours of computing time. Looking back over previous Congresses would take even longer.

We looked for a way to narrow down the group of bills to evaluate. The first approach we tried, looking at similar bill titles, goes a long way toward solving the problem.

Similar Titles, Similar Bills

It turns out, when a new bill is introduced with the same purpose (and often by the same sponsors), the new bill is often given the same title. Sometimes only the year is changed. So we have the ‘SHOP SAFE Act of 2020’ and the ‘SHOP SAFE Act of 2021’; the ‘Freedom for Farmers Act of 2018’, the ‘Freedom for Farmers Act of 2019’ and the ‘Freedom for Farmers Act of 2021’. If we simply remove the year from the title name, and search through an index of titles, we can find many of the bills that are similar to a given bill.

Searching for titles highlights another kind of relationship between bills: one bill incorporated into another. Larger bills, particularly in recent years, may roll up many smaller bills. The overall bill may have one or two titles, but there are many titles within the bill that refer to only a portion of the bill. The fact that another, smaller, bill shares a title with only part of the larger bill is itself important information. For example, H.R. 1 (117th) has the overall title ‘For the People Act’. Within it are dozens of other titles which refer to a smaller portion of the bill. Many of those titles are shared with other, independent bills. The ‘For the People Act’ may share only a small part of its text with each of those bills, while the entire smaller bill is included by the larger act. Below is an entry in the BillMap application showing many of these titles within the ‘For the People Act’.

Our first pass at processing bills now looks at the two kinds of title separately. If a bill matches the ‘main’ title of another bill, it is probably a better match for the whole bill. If it matches one of the titles for a portion of the bill, it is likely that the smaller bill (or a version of it) was included by the larger bill.

Matching bills by title alone captures a large part of what people mean by finding similar legislation.

However, we would still like to track bills where the title is changed, or only portions of a bill are included in another bill (without the title). For those cases, we use a specialized ‘more like this’ search, a kind of Spotify or Amazon ‘Recommendations for You’, made for bills.

Searching bills by section

While comparing bills two at a time is very resource-intensive, there are shortcuts. We start by creating an index of bills and use a specialized algorithm to find text similarity (see ‘More Like This’ query in Elasticsearch).

We search the index with parts of each new bill. We don’t search the index using the whole bill text, for the same reason you don’t usually type a large text into Google’s search box: we’d get too many false positives. Instead, we break each bill down into its logical building blocks, sections. We then search each section against the index, find which bills have similar sections and then combine the results at the section level to find the whole bills that match. This approach has a number of advantages: we get granular information about what sections of other bills are similar to the sections of the current bill; and by combining that information, we can find the bills that are more similar overall. Below is an example from H.R. 1 (117th) showing, for each section of the bill, a list of other bills that have similar sections.

Round 3: bill-to-bill comparison

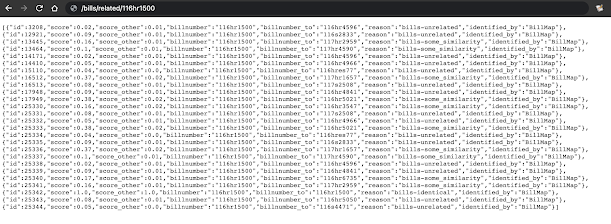

The first two stages of our process find bills with similar titles and similar sections. The first stage is narrow, finding only bills that have the same title (minus the year). The second stage is wider, finding bills that have some similar text in their sections. The nature of that text search is that it is over-inclusive, and returns some bills that don’t actually share much in common (other than some phrases), with the original bill. To add precision to our results, we take that list of similar bills (about 20-30 bills) and do a pairwise comparison with our original bill. While this is still time consuming (up to 30 seconds for some bills), it takes much less time than comparing against the tens of thousands of bills we started with. This last stage has another advantage, it allows us to evaluate the textual similarity of the bills. We can describe this on a scale (e.g., 0 – 100) or with categories. For BillMap, we label the pairs ‘identical‘ (more than 95% text match), ‘nearly identical‘ (more than 80% text match), ‘some similarity‘ (between 10-80% text match) or ‘unrelated‘ (less than 10% text match). Additionally, when one bill is completely included in another larger bill, we can determine that it is ‘included by’ the other bill; and the larger bill ‘includes’ the smaller one.

Depending on the kind of information a person is looking for, each of these categories, as well as the information about title or section matching, may be relevant. In the BillMap application, we show this information in a table: for each bill, we return up to 30 bills that meet one or more of these criteria, and list all of the categories in a list of ‘reasons’ we consider the bills similar.

Build Your Own

One of the goals of the BillMap project is to create processes that could be used in other projects to show information about bills. Toward that end, I’ve built a separate API interface for the bill title and related bill data. Using the interface, you can search by bill number to find the bill’s titles, search by title to find other bills that have the same, and find bills that have matching section data (results shown in JSON below):

I will describe this interface and its potential uses in more detail in a future post. In the meantime, you can read the technical details of the API in the project documentation on Github.